Helio Courier: From Tennis to Tundra

- Will Day

- Jan 8, 2022

- 12 min read

Updated: Jan 11, 2022

by Will Day, Alaska Airmen's Association

The Tennis Court Airplane

Imagine a world where helicopters have been replaced by small, quiet airplanes. Wealthy white collar workers head for parking lots instead of helipads, where they board a plane that easily clears the nearby treetops—not quite a helicopter, but close. They float across town at 135 miles an hour and drop into their destination parking lot so quietly, that only the closest pedestrians notice. There’s no ear-splitting propellor noise, no runway, and less risk and cost than using a helicopter. This was the dream that eventually birthed the Helio Courier.

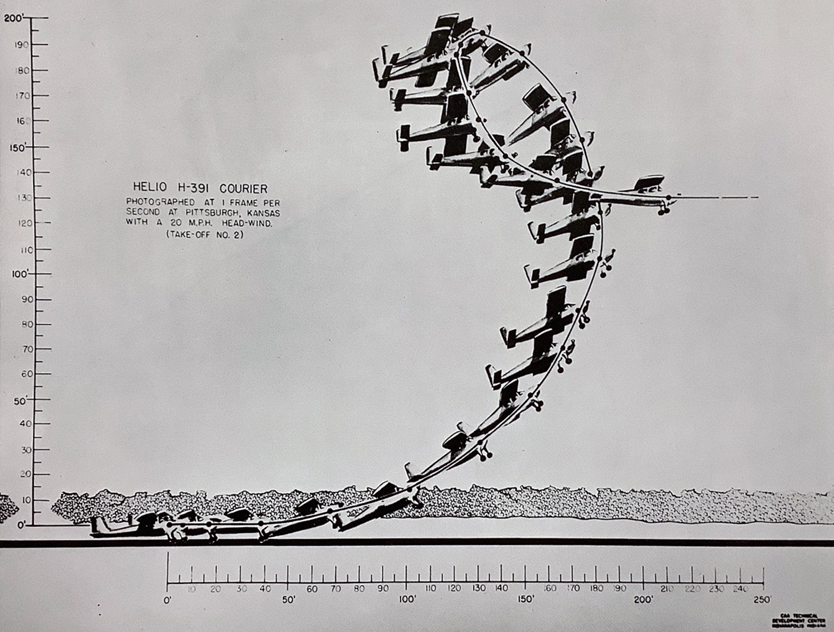

In the late 1940s, Dr. Otto Koppen, an aeronautical professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, designed the Helio-1 “Helioplane” using the cabin fuselage of a Piper Vagabond. This concept aircraft—built to demonstrate safe Short Takeoff and Landing (STOL) capabilities—could take off from a Harvard tennis court, earning it the moniker “Tennis Court Airplane.” A short while later, Dr. Koppen and Harvard business professor Dr. Lynn Bollinger founded the Koppen-Bollinger Aircraft Company, which would soon evolve into the Helio Aircraft Corporation. Together they advanced Koppen’s design and marketed the Helio Courier as “everyone’s safety plane”, a faster, more affordable, and safer alternative to the helicopter. Their goal was to produce an aircraft that met the following conditions:

Fully controllable at 30 miles an hour.

Stall and spin proof.

Takes off in 100 feet or less and climbs at full gross weight in no-wind conditions.

Clears a 50-foot obstacle in less than 300 feet from a standing start.

Lands within 100 feet after touchdown.

Cruises above 100 MPH.

Operates as quietly as an automobile.

Sells for approximately $500 more than conventional light aircraft of the time.

The Helio Courier design was at the cutting edge of aeronautical engineering when it was first produced. The plane employs autonomous leading-edge slats, flaps that span 74 percent of the wing, deep-chord ailerons, and aileron-deployed lift interceptors. These features combine to maximize lift and maintain exceptional maneuverability at ultra-low speeds. The slats deploy automatically when flying slowly, preventing the wing from stalling; they retract when accelerating to reduce drag and allow higher cruise speeds. Lift “interceptors”, greatly reduce the lift over the high wing during steep, slow turns. The diminishing lift causes the high wing to bank downward until aileron input is reduced, balancing the wings—allowing the aircraft to turn when the ailerons have lost most of their authority. In short, the Helio uses automatic, complex systems to retain control of the aircraft at slow speeds while allowing the pilot to fly the plane intuitively—greatly reducing the likelihood of fatal pilot error.

ADVERTISEMENT

While the Helio Courier succeeded in meeting performance expectations, the financial criterion was grossly optimistic. In 1954, the Helio Courier, model H-391B, sold for $24,500, nearly three times the cost of its closest competitor: Cessna’s 170B which sold for $8,500. "At that price, the Helio was destined for only special niche markets such as the military, law enforcement agencies, a few well-heeled individuals and isolated corporate operators who could afford the initial steep sticker price as well as expensive maintenance fees." (Rowe, 2006).

CIA Use

“All airstrips in Laos were classified as ‘Helio’ or ‘Others.’”

The Central Intelligence Agency purchased twelve to fifteen Helio Couriers in 1957. Lieutenant Colonel Harry C. Aderholt test flew the Helio and immediately knew he’d found “what the CIA needed to exfiltrate people from hostile territory and to support partisans behind enemy lines.” (Dorr & Borch, 2013) The aircraft’s utility under a variety of dynamic circumstances made it greatly appealing for covert operations. It could fly relatively quickly and land in just 120 feet on the roughest strips—even curved, mountain ridgetops. “All airstrips in Laos were classified as ‘Helio’ or ‘Others.’” (Robbins).

Vietnam War

In the 1950s, the U.S. Air Force ordered three Helio H-395 Super Couriers and renamed them “U-10”. Legendarily, one of these aircraft touched down in the Pentagon’s courtyard to make an impression on military and civilian officials. (Dorr & Borch, 2013) If it happened, the dog and pony show must have paid off, because the U.S. Military became a major Helio customer.

Counterinsurgency and unconventional warfare demanded a relatively quick-moving aircraft that could travel long distances, carry heavy loads, and endure the rough handling of wartime flying. The Helio outperformed helicopters in each of these areas. This made it the ideal tool of the time for a variety of aerial operations in the Vietnam War. Helio pilots transported personnel and cargo. They escorted helicopters, flew reconnaissance missions, and conducted psychological warfare. In the latter case, “the U-10 gained the nickname 'Litterbug,'” because, “propaganda leaflets could be discharged through a chute in the aft righthand door." (Rowe, 2006)

“The USAF used enlisted men as forward air controllers in Laos in 1963. They were called Butterflies and flew on Air America Helio Couriers and Pilatus Porters.” (Cates, 2017) Allegedly, the Butterflies impersonated civilians to preserve the impression that the United States was not associated with the operations. They were charged with marking targets to minimize non-combatant casualties—an easily accomplished task in the quiet and slow U-10.

During the war, the military foreshadowed what would become the aircraft’s inevitable destination. The “Helio U-10s (were used) by the U.S. Army to police large tracts of territory in Alaska to enforce an anti-drug-smuggling campaign. The Helios were used to counter the flow of drugs (most notably heroin) coming from the Soviet Union and Red China via the 50-mile-wide Bering Strait.” (Rowe, 2006)

Migrating North

The end of the Vietnam Era marked a rite of passage for the Helio Courier. Military demand for the slow-flying plane disappeared, and the Helio Aircraft Corporation was forced to adapt. In the mid-1960’s, DK McDonald, an insurance broker in Seattle, wanted a Helio distributor on the West Coast. He chose Seattle because of its ideal placement as a hub for the western states and Canada. Like his military predecessors, DK went about gathering support for the Helio in grandiose style. He held a big party on a golf course in Seattle and invited local investors. Everyone stood on the grass of one of the holes when DK announced he had something exciting to reveal, "it's quite an airplane!" Moments later, to the audience’s great surprise, a Helio Courier descended silently over the treetops and came to an abrupt stop on the golf course. The demonstration left little doubt in the minds of those present that they had witnessed the future of aviation.[1]

Sometime after the memorable demonstration, DK McDonald approached Dennis Branham—expert pilot, renowned hunting and fishing guide, and lodge owner in Alaska. DK urged Dennis to consider the Helio, as it would surely meet his bush flying needs. Stolairco, McDonald’s now-shuttered Helio distributor in Seattle, encouraged Dennis to become the Alaska sales representative for the aircraft. In 1966, Dennis was finally swayed and ordered a factory-new H-395A, N4195D, for $42,000—nearly $350,000 today and almost twice the current resale value. The purchase was clearly a sound investment, as Chris Branham, Dennis’s adopted son, still flies the plane today for his family’s lodge business. Dennis went on to sell a handful of Helios over the years, including one to famed bush pilot, Bob Reeve.

"To hell with a Cub, you can have it!"

The Branham family, which now operates several popular lodges in Alaska, still uses a fleet of Helio Couriers to get in and out of small, idyllic hunting and fishing destinations. Chris recently opined why he prefers the Helio in an interview for this article:

While hunting, "I'd go in there with a Super Cub, go in and out. But the problem was you could only put so much in a Super Cub. So, the flying time was almost double. If I had a hunting camp that was a half an hour away, I'd have to take all the gear and the guide and all the food and the groceries. Take him, come back get the client and his gear in the super cub. And I thought, “Gee, this is a pain in the ass!” (Branham, 2021)

Early on, Chris put the Helio on "balloon tires" and flew it empty into Super Cub strips. He was surprised when it landed gentler than the Cub and could easily handle the same short airstrips. Confidence bolstered, he took it into a challenging Cub-strip. After a few touch-and-goes, he thought "I can do this." Sure enough, the landing was relatively easy, and he knew then, "to hell with a Cub, you can have it!" (Branham, 2021). The Helio Courier would go on to become the primary workhorse of his operations.

Wright Air Service and the Pipeline

The Branhams weren’t the only early adopters of the ultra-capable bush plane. Al Wright—founder of Wright Air Service—had read about Helios in a magazine, and in the mid-1960’s, he’d hired a pilot who’d flown them in Vietnam. The pilot convinced Al to trade his Cessna 180 and some cash for an H-250. So, Al employed Bob Bursiel to ferry the Helio from Great Falls, Montana to Fairbanks, Alaska.

Bob Bursiel Flying Helios for Wright Air Service

“There were no other Helios in Fairbanks. The kind of flying Al had been doing at that time included flying villagers, miners, trappers, and hunters, mostly with a Cessna 180. Al liked the idea of the bigger cabin for loads like moose and gear and the fact that the Helio would be capable of landing on short gravel bars and other off runway locations.

“Over the years, Al’s hopes for the Helio Couriers proved true. Its passengers have included hikers, recreators, homesteaders, hunters, villagers, and floaters. It can carry more of a load than the smaller bush planes like Super Cubs and Champs. Fish and Game personnel particularly liked using it for fish, moose, and sheep surveys. The Helio’s ability to fly safely at low speeds enabled it to use less room to turn. The good visibility due to the high wings and lack of struts to block the view was also a plus for spotters.

“Distinct advantages of the Helio Courier for Pilots and Operators include safety features such as its steel tube construction around the cockpit.” Helios also are unlikely to stall[2] and spin since flaps and slats make possible a much slower landing speed capability to lessen that potentiality. During an engine failure or other forced landing scenarios, this slower landing capability results in much greater safety for those on board.” (Bursiel, 2021)

Bursiel’s quote implies stalls and spins are possible in a Helio Courier. It should be noted that Helios are impossible to stall and spin in the conventional sense; leading edge slats and limits to stabilator travel prevent a configuration where flow separation over the wing can occur.

“A personal example of this involves a Helio I was flying back to Fairbanks when the engine completely failed while over a forest. As I scanned the area below, I spied an area where the tall spruce trees were thinned out and alder saplings filled a small meadow area up ahead. I was able to fly the Helio to that point as it descended. When the plane stopped, the damage to the Helio included the ruined engine and damage to the wings, prop, landing gear, and slats. As for me, I opened the door and stepped down to the ground without a scratch.” (Bursiel, 2021)

Once the pipeline was completed, Wright Air Service was contracted to conduct daily aerial surveys along its entire length. Each morning, a pilot would take a Helio from Fairbanks to Valdez and back. Then, a second pilot would take the same plane from Fairbanks to Prudhoe Bay and back. Wright Air Service outfitted their Helio with a camera so that pictures could be taken of any animals near the pipeline, anything that seemed suspect, or any people or vehicles along the right of way. The slow speed capability allowed pilots to fly very slowly but still safely when taking pictures. The ability to cruise relatively quickly allowed them to complete this mission every day. If the weather was bad, excellent off-airport landing capability allowed the pilot to find a spot to put it down virtually anywhere and wait out poor conditions. Al said over two years they only missed three days of completing this daily survey. Over subsequent years, Wright Air Service operated up to seven Helios at a time, four of which are still in use today. (Wright, 2021)

Denali

Lowell Thomas Jr., the former State Senator and Lieutenant Governor of Alaska, bought his Helio Courier in 1969 for his air charter business, Talkeetna Air Taxi. Lowell chose the Helio, N6319V, because he wanted a STOL plane for mountaineering. “He connected with Don Sheldon sometime in the mid-1960s and flew a lot with Don, which is when he fell in love with Denali, and he began to spend most of his mountain flying time up there.” (Donaghy, 2022) He had it equipped with a turbocharger, so he could fly it up to 14,000 feet on Denali. Lowell was an avid writer who thoroughly enjoyed recounting adventures he shared with N6319V. Here are a few of those stories:

Close call over Denali

“It was late winter of 1984. Missing was Japan’s legendary adventurer Naomi Uemura, who was attempting the first winter solo… My partner, Doug Geeting, and I were doing his flying from Talkeetna. I had last glimpsed Naomi’s red-clad figure through a cloud break on a Sunday afternoon as he was climbing that icy slope from 17,000 ft. to Denali Pass. One of the two Japanese TV cameramen with me in my plane talked briefly with him over my citizen band (CB) radio; he said he was making his final ‘dash’ for Denali’s summit. Days of poor weather passed with no sign of Uemura; the search was on by Doug and me, and by mountain rangers of the National Park Service.

“My close call came during a solo flight, on oxygen, at 20,000 ft. while searching the north slope of Denali’s south peak, the upper Harper Glacier, for the missing climber. The air was smooth, no visual cues of wind which I knew was on my tail as I flew west to east. Just as the plane reached the eastern face of the mountain, the bottom fell out. Plane and I were in freefall, tumbling down nearly out of control. My head banged the cockpit ceiling despite my seat belt; loose things in the back came floating forward, and in a matter of seconds we had dropped from 20,000 to about 14,000, miraculously right side up and over the northwest fork of the Ruth Glacier. The airflow out of the west had swooped up Denali’s west flank then plunged back down the other side – an aerial Niagara Falls. Lucky for me the plane’s forward momentum carried us beyond the ice and rocks of the East Buttress. That was just one of many learning experiences.” (Thomas Jr.) Despite the Helio’s ability to reach those altitudes, Uemera was never found.

Lowell and Charles Lindberg

Charles Lindbergh came up to Alaska in a rare public speaking role in 1968. He addressed the legislature in Juneau on the need for conservationists and hunters to work together for the sustainability of wildlife, particularly the wolves and polar bears hunters had been shooting from airplanes. Lowell wrote:

“The year after his talk to the legislature Charles returned with a New York Times senior reporter while writing a story about environmental degradation in all the 50 states… Charles joined me for a flight in my Helio Courier over Chugach State Park and on down to Kenai, looking for moose.

“The flight was one of my most memorable––flying that famous aviator as a passenger! I was so concerned about a smooth operation that I went to the plane several hours in advance… to clean the wings of frost, preheat the engine and give it a pre-takeoff runup, and do a most thorough preflight check. When Tay (Lowell’s wife) drove up to the plane with the General (he was promoted to BG during WW2) I told him all was ready. Without saying a word, he slowly walked around the plane, looking at its parts with full attention. When he reached the horizontal stabilizer, he took the left side end in both hands and shook it up and down three or four times, then let it go, watching its vibrations closely. I wondered what that was all about, but he didn’t say. Perhaps he knew that the stabilizer was secured to the fuselage with only two bolts, and wanted assurance that they were sound?

“Leaving the Chugach for Kenai, Charles asked to take the controls. No argument!! He did a few steep turns, then pulled the nose up nearly vertically, keeping the power on, until I thought the plane would slide down on its tail. Just before that happened, Charles lowered the nose to recover from the stall. Now that was something I had never done; no reason for it (the plane was not approved for acrobatics).” (Thomas Jr.)

Setting roots in Alaska

Since its inception, the Helio Courier’s ownership has migrated across the United States. The Helio Aircraft Corporation began at the Boston Metropolitan Field in Canton, Massachusetts, where the company produced the first iterations of the aircraft. Production shifted to Pittsburg, Kansas in 1955 and remained there until ceasing in 1984. Since that time, the type certificates passed through several different owners. In 2020, Helio Alaska, Inc. acquired the Helio Courier’s type certificate and moved to a hangar in Birchwood, Alaska. In a sense, they have reunited Helio headquarters with the largest concentration of the still-operational aircraft. Today, 37 Helio Couriers operate in Alaska, making up 31% of the 120 aircraft currently registered in North America. (Federal Aviation Administration, 2021)

In May of 2021, Lukas Stutzer and Abraham Harman who own Helio Alaska, Inc. displayed their 1972 Courier, N62JA, at the Great Alaska Aviation Gathering. They posted educational signs on each of the parts that make the aircraft uniquely capable as an Alaska bush plane. As I wandered around the display, I wondered how such an ideal workhorse had fallen out of production. Why was such an obviously useful aircraft not thriving like Piper’s Super Cub or Cessna’s 185? As I watched Stutzer and Harman chat animatedly with passersby, I pondered what the future might hold for this aeronautical masterpiece now that its destiny lies in their hands.

______________________

Footnotes:

[1] A dramatization of an account by Chris Branham.

[2] Helios are impossible to stall in the conventional sense; leading edge slats and limits to stabilator travel prevent a configuration where flow separation over the wing can occur. Large flaps are one of many devices that allow the Courier to fly at low speeds.

Sources:

Branham, C. (2021, October 20). (W. Day, Interviewer)

Bursiel, L. (2021, October 29). (W. Day, Interviewer)

Cates, A. (2017, May 25). Air America History. Retrieved from Air America: https://www.air-america.org/air-america-history.html

Donaghy, A. (2022, September 9). (W. Day, Interviewer)

Dorr, R. F., & Borch, F. L. (2013, September 29). U-10 Helio Courier Was Unsung Hero in Vietnam. Retrieved from www.defensemedianetwork.com: https://www.defensemedianetwork.com/stories/u-10-helio-courier-was-unsung-hero-in-vietnam/

Federal Aviation Administration. (2021, 12 15). Aircraft Inquiry. Retrieved from FAA Registry: https://registry.faa.gov/aircraftinquiry/Search/MakeModelResult

Gallery. (n.d.). Retrieved from Wright Air Service: http://www.wrightairservice.com/about-us/gallery/

Robbins, C. (n.d.). Air America.

Rowe, F. J. (2006). The Helio Courier Ultra C/STOL Aircraft. Jefferson: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers.

Thomas Jr., L. (n.d.). Account from Anne Donaghy via Email.

Wright, A. (2021, September 1). (L. Stutzer, Interviewer)

Comments